Dispatch: Raven Editions attends the Mid America Print Conference (MAPC) at Kent State University

Be Loud! A Culture of Visual Language.

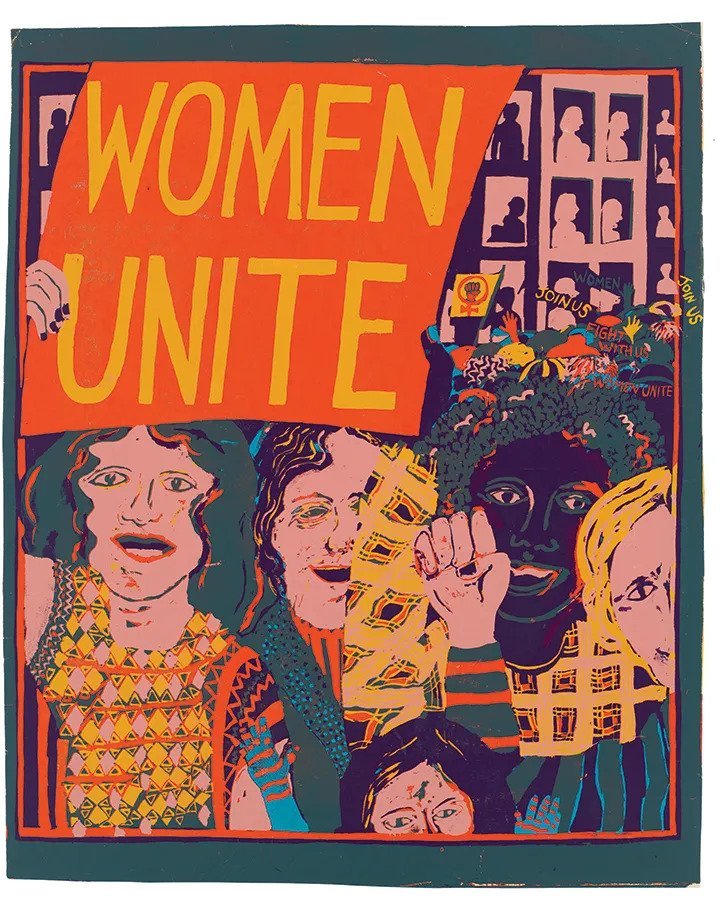

For centuries, printmaking has given a voice to the voiceless, encouraging social change and influencing a whole culture of visual language. This year’s Mid America Print Conference highlights that in The Power of Print: Resistance, Revolution, Resilience.

By its very nature, printmaking has represented a voice of politics and a subculture of belonging and resistance while offering a means of documenting and preserving the histories and stories of those oppressed. For keynote speaker Amos Kennedy, an artist & printmaker from Detroit, and many other printmakers in attendance, art equals activism. Printmaking expresses the residual energy of the artist’s intentions with the work. Each work represents a labor of making that is as equal to the labor of politics that the work represents.

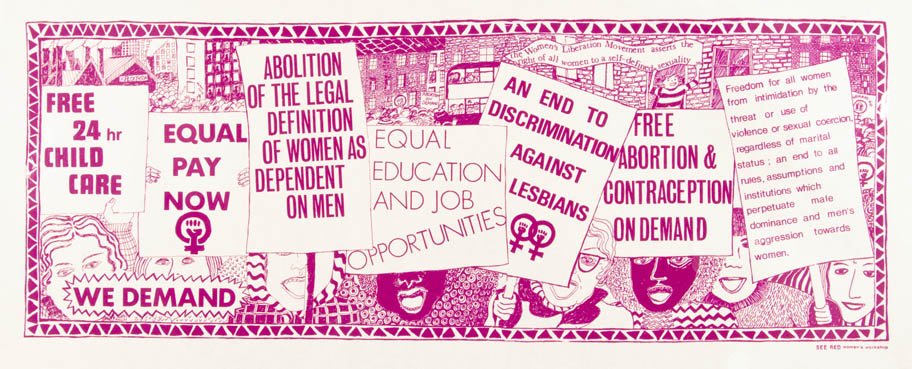

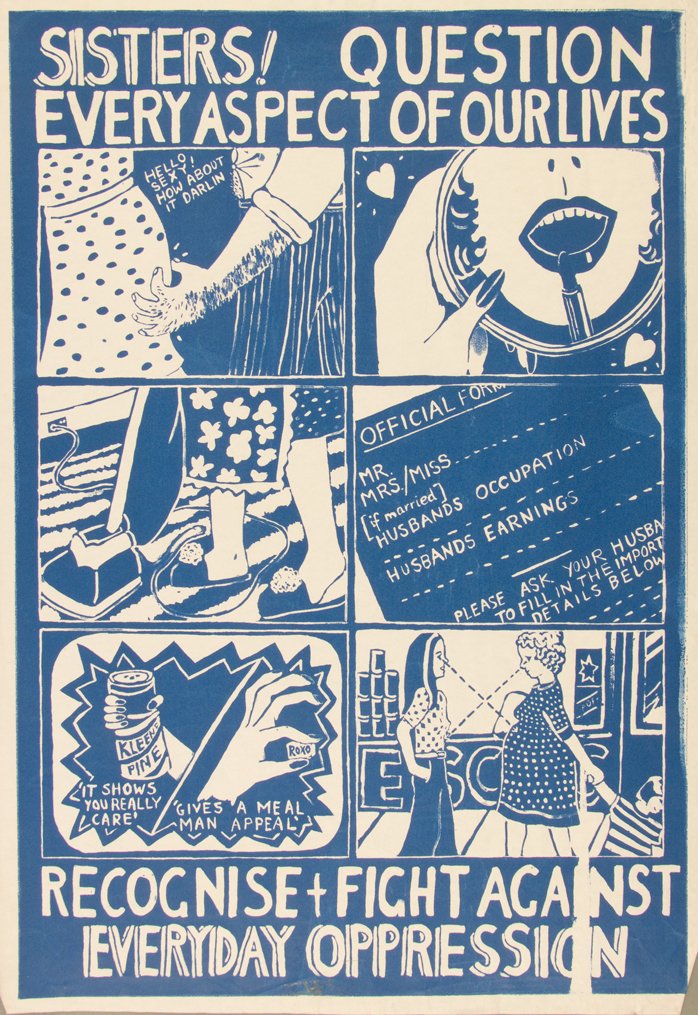

This tradition continues today as printmakers use their art to deepen the conversations surrounding social justice and activism. This notion was emphasized by a panel entitled Cheap + Easy: Zines, Posters, and Alternative Histories, led by Vin Caponigro of Snake Hair, a print studio currently based on occupied Massachusett and Wampanoag land. The panel began with a brief history of printmaking as told by the printers whom history often forgets, like the Red Women’s Workshop, a screen printing studio started in 1974 by a feminist collective in London, England. The other panelists, 3Gatos Press, Brett Colley, and local activist/artist Josh Graupera, discussed how printmaking impacts their communities. 3Gatos Press, a contemporary print studio in Mexico, talked briefly about the do-it-yourself aspects of zine-making they share with their audience and their efforts to diversify engraving, and the scope of its procedure and application.

Brett Colley, a printmaking instructor at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, MI, described teaching techniques that encourage students to forget the politics of politeness and instead focus their attention on documenting democracy, inclusion, and community history. Josh Graupera, a local Lancaster, PA activist/artist, discussed connecting visual art and community organization to effect change. Graupera works with Seed Project, a local community initiative working to bring neighborhood-centered artworks and collaborations to Southeast Lancaster City. Seed Project regularly uses zines to share initiative resources for radical self-help, community-help, and planet-help. Additionally, Graupera talked about his work as the Creative Arts Coordinator for YASP, or The Youth Art & Self-empowerment Project, which teaches young people facing incarceration to express themselves creatively through zines and other art-making.

The conference paired long-form panels with hands-on demonstrations from renowned print instructors and artists. Of these scheduled demos, the most popular was a laser-cut jigsaw woodblock demonstration organized by Lari Gibbons. Gibbons directs the Print Research Institute of North Texas, P.R.I.N.T. Press, and teaches printmaking techniques, including etching, relief, and monotype, at the undergraduate and graduate levels. The demonstration encompassed her professional work exploring the environmental philosophy and versatility of printmaking. She presented the utilization of a high-powered laser cutting as an alternative to manual carving, highlighting its accuracy, low-end energy use, and lowered production costs that make it a more eco-friendly alternative in printmaking.

Other panels, like Removing Barriers in a Studio Practice, discussed the aspects of printmaking that many artists still find lacking, like accessibility. For artists like Chelséa Clarke, an instructor at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, their disabilities greatly affect their ability to create. As lead panelist, Clarke asked fellow panelists Meg Pohold, Heather Huston, and Zoe Steinberg, “Why do we continue to place the most value on the least accessible processes when we widely consider ourselves the most democratic discipline?” Artist and student Zoe Steinberg discussed making prints that challenge people's inability to make space for them and their disability. They spoke about having missed a class because their wheelchair was caught on the sidewalk, leaving them trap until a passerby assisted. While embarrassing, the experience prompted Steinberg to consider how artists can use their barriers to create, resulting in a new edition of works formed from the tire marks of her wheelchair. The paint splattered wheels becoming a crafted autobiography of survival and invisibility.

Meg Pohold, an instructor at Laney College in California, talked about using found objects in printmaking. As an artist with PTSD, Pohold emphasized the importance of responding to trauma with social collaboration and creation, whether that means working with other artists or the objects of others. Pohold’s practice relies on found photographs of strangers, which she uses to create new narratives about trauma juxtaposed with the unfamiliar people and memories recorded by the photographs. These “ghost prints” represent an imaginative space for Pohold, where she can explore her childhood trauma through creation and destruction. Finally, Heather Huston, an instructor at Alberta University of the Arts, Canada, argued in favor of adaptive workspaces. Her speech emphasized the importance of rethinking our expectations for creation so that they aren’t centered around the abilities of able-bodied artists. This is especially important for instructors and studio managers who need to create space and change their perception of disabilities to anticipate the accommodations an artist might need. Where accommodation equates equitability, printmaking can become an ally in building a culture of accessibility.

The conference, The Power of Print: Resistance, Revolution, Resilience, argued for art as a subculture of belonging. Printmaking has and continues to demand inclusivity, representing individual voices while also encompassing a collective desire for change. The do-it-yourself culture of printmaking has made it an accessible and affordable avenue for artists, activists, and politicians alike. This makes printmaking one of the most powerful catalysts for engagement with issues of environmental, cultural, and economic sustainability.